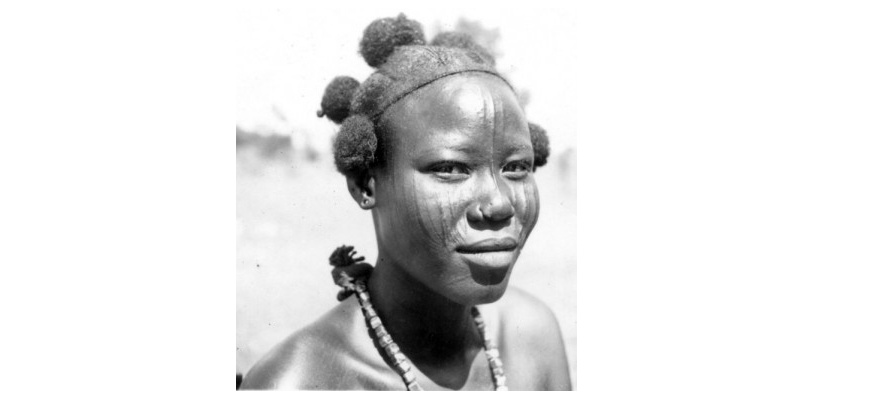

Tribal Marks: Cultural Treasure or Barbaric Practice?

Tribal marks are an age-long art common to the Western part of Nigeria. The Egba, Nupe, Ilaje and other Yoruba tribes commonly use these marks and designs as a form of identification, beautification and protection. There are two different types of marks: ila (the well-known facial scars) and ona (also known as “local tattoos”). Both are created using a sharp instrument such as razor blades, knives or glass. Flesh is cut from the skin to create a gash, which later heals and leaves a permanent pattern on the body. Snails (known as Igbin in Yoruba), a popular delicacy in Nigeria, are very important to tribal mark artisans, as the liquid they secrete is used to soothe the pain caused by the instrument used to make the incisions. The unique colour of the ona comes from various pigments such as charcoal.

Tribal marks were used as a source of identification in times of war or migration. There are different styles for different tribes; for instance, the Pele style, which has three versions: Pele Ijesa (thick, half-inch vertical lines on both sides of the nose down to the mouth); Pele Ekiti (quarter-inch horizontal line) and Pele Akoko (quarter-inch vertical or horizontal lines). An individual’s tribe or family typically dictates the pattern in which tribal marks are inscribed on their face, stomach or legs. The ona designs typically have symbolic or decorative significance connected with various life stages such as puberty and marriage. Specific families are charged with the responsibility of creating these marks. These families are called Olowo Ila or Omo ile Olona (meaning “one who’s wealth is gotten from the art of tribal marks” and “one born into a family of tribal designs” respectively). These household names are also used to sing their praises. The skill of making these marks is passed from one generation to another. Most Yoruba women aged 80 and above have tribal marks on their bodies, as they were considered a sign of beauty in their youth. My grandmother has words tattooed on her chest, arms, and legs. These words are orikis or praise words, which are complimentary phrases about the person they are inscribed on, such as Apeke (“called to be cared for”) and Àdùké (“people will fight for the right to spoil her”). A closer look at her right arm revealed a heart with an arrow through it - she must have been in love when she got it. Other parts of her body had drawings that I couldn’t decipher. I was struck by how my grandmother was a record of history and culture, whether through her tattoos or the stories she has passed down to me about the Obas of Lagos, or the special songs in praise of the king. Despite their long history, some Nigerians believe the practice of scarification should be stopped, whether because they perceive them as “barbaric” or as unfashionable and antiquated. I recently spoke with a young lady from Edo State in her mid-twenties, and she expressed disapproval at the practice. She was made fun of as a child for the seven marks evenly placed on both her cheeks. She received these because she was thought to be an abiku (a term used to refer to a child who is stubborn, sickly, or dies and returns back to life as punishment to their parents for offending the gods). The severe scars on the back, ears, face are thought to lead to a rejection of the abiku by its spirit friends, who will then let the family live in peace. Another young man from Badagry in Lagos State said he loved his tribal marks (thick scars on both sides of his face) as he felt they made him unique. He stressed that they were part of our heritage, and were therefore worth preserving. Click through the slideshow to see different examples of tribal marks: [slideshow_deploy id='2317'] What do you think? Should tribal marks be abandoned or continued? Share with us in the comments! Photograph sources: Dynamic Africa, Nigerian Nostalgia Project, TribalPunkApparel