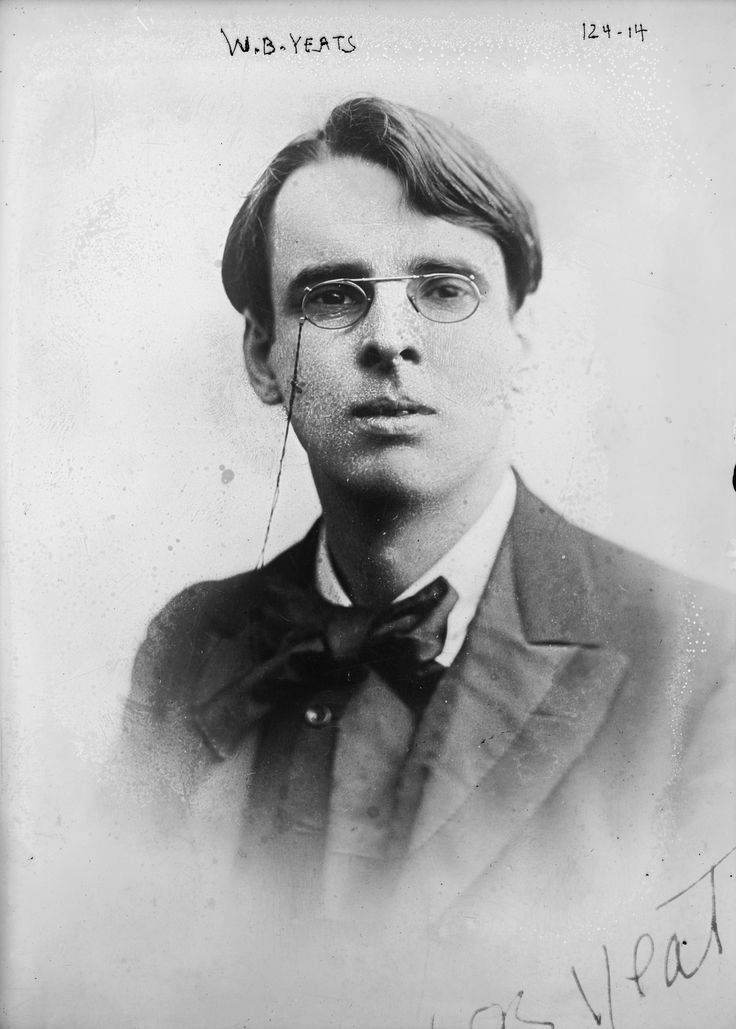

WB Yeats’ Easter, 1916: An Overview of Bravery and Heroism

To understand WB Yeats’ poem Easter, 1916, one needs to first understand the background of it, thus the causative effect of the context. In truth, the poem actually revolves around a true history of Irish independence. In their genealogy against the British people, there was a resistance that surfaced in 1916 on an Easter week which was later tagged as the Easter Rising. It is this history that gives birth to the title of the poem, wherein Easter is to foreground the Easter Rising, and 1916 is to foreground the year the rising took place. Furthermore, it is important to know that the Easter Rising was a resistance from the Irish people with the aim of gaining independence for the Irish Republic. This rising happened during the same time the United Kingdom was fighting World War I. However, one of the most interesting parts of the story is the fact that this uprising was indeed led by someone who looked so ordinary — a schoolmaster, Patrick Pearse. A look into the poem itself reveals to us how most of this resistance is led by people whose lives are extremely mundane. Thus, this essay is going to review WB Yeats’ Easter, 1916 through an overview of heroism and bravery.

To start with, the first stanza of the poem introduces the poet’s persona and the rebels to the readers. However, the striking thing about the persona is that they never look like rebels, in fact, he sees them as a joke — people he can make a mockery out of “to please a companion around the fire at the club”. This is probably why in the two encounters he reveals, he only greets them with either a nod and polite meaningless words, or a short stop and polite meaningless words. In short, he never sees these people beyond mediocrity. However, the plot twist sets in, and everything changes: a terrible beauty is born.

In furtherance to giving the terrible beauty that is born more context, the persona foregrounds the character of these rebels to reveal how ordinary they really are — how unfit they are to be heroes. For instance, he mentions a woman who when she was young and beautiful spent her time in leisure pursuits like hunting, but then suddenly became one who became extreme with political arguments. Likewise, he introduces us to another man who was a poet and schoolteacher. Then another who was a poet and critic. Then another whom he perceives as being a proud drunkard — he mentions how this particular man has done something bad to people he holds dear, but how he still has to immortalize him in his poem. Looking into how these people who once had nothing but ordinary lives became a part of a revolution is exactly what Yeats means when he says a “terrible beauty is born”. That is, although their devotion to joining the resistance got them all killed (terrible), he can’t deny the truth of their bravery and heroism (beauty).

What is more, the persona seems to be unsure whether to praise them for their bravery or to condemn them for their foolishness. For instance, in the third stanza, he revolves around how their decision to join the resistance changed them completely. How, in the process of the revolution, they become dead in their humanity before they even died at all. This is why he uses the word “stone” to typify how unchanging they were amidst every other thing. That is, the horse, the cloud, and even the stream. He explicitly exposes it immediately in the first line of the last stanza, that “too long a sacrifice can make a stone of the heart”.

Finally, although Yeats seems to be going on and forth between praising these so-called rebels or condemning them, at the end of the poem, he immortalises their bravery and heroism through his poem by exposing the readers to their names. The names of these heroes include MacDonaugh, MacBride, Connolly, and Pearse.